I’m gonna break with my 61-word format and post up this long-form article. I hope it helps you all think a little bit about the comic book buyer’s market and how it has evolved with the evolution of technology.

I’m gonna break with my 61-word format and post up this long-form article. I hope it helps you all think a little bit about the comic book buyer’s market and how it has evolved with the evolution of technology.

I keep reading comments all over the Internet that talk about the disgust with “all these variant covers” and the impending implosion of the variant market. Let’s get a little into human psychology and explain why allusions to the 90’s market are unfounded in today’s setting. In fact, let’s break with the typical angst of the Internet and have an intelligent conversation and identify the factors. Bear with me here.

First, let me blow your mind: the trend toward variants in comics has nothing to do with comics at all. It has everything to do with the established trend of limited run exclusives. These aren’t new, they are just now easier for manufacturers to produce. We Americans crave exclusives. We love to have something that sets us apart from everyone else. The sole purpose driving the want for the riches of the world are to be able to get the things that no one else can have. A bajillion dollar home, a car that has 900 horsepower, a stole that’s made from some rare animal pelt. All the same thing, the drive to be part of an exclusive club. Check out this article on Business Insider for a little evidence.

Variants tap into that same vein. Having one of something that is desirable fulfills this urge to own what very few others do. Face it, we all have a book that we love to show off because no one else can. Heck, let’s take a look back at those golden and silver age grail books. Even though no one wants to face it, the condition ranking for these can be considered a modification variant concept. Being in the 9.0-grade club for a Fantastic Four 52 nets you great money, but it also puts you into a rare club. Here’s where I will continue to upset some of you. A 1944-printed comic book has no more intrinsic value than a comic book that was printed yesterday. It’s still essentially paper and ink. No precious metals are derived from the degradation of the materials as time ticks away at its molecules.

Like all things, a books’ worth, variant or not, is dependent on what someone else is willing to pay for it.

Second, let’s talk about why variants are so prevalent now “more than they ever were”, and why the 90’s allegory doesn’t fit in the narrative.

In the early era of mass production, it would have been a financial imposition to burden a manufacturer to create a limited run of anything. A die that is used to cast a 3D mold of an object has a specific cost, regardless of how many are produced, so there is a delicate balancing act trying to balance the object price, the cost to produce it, and what people are willing to pay. The same was true about printing presses, bottling techniques, and assembly line processing. The fabrication costs would put the price so high that no one would want that one-off item. Examples of this are some limited car prototypes that manufacturers offer to the public that cost millions of dollars. Why, because they can’t spread the R&D (research and development) across thousands of vehicles.

In the 90s, there were a lot of fancy tricks at play to create the glossy, holographic, 3D, prism, embossed, and other flashy books of the day, but they still had to print them en masse. Buyers then didn’t have access to print runs like we do now. When they found out that EVERYONE had their book, they jumped ship, ergo, the inevitable crash.

Let’s jump ahead to today. One-off production is cheaper than ever. 3D printed dies, robotic driven manufacturing lines, and dye sublimation printers are just some of the examples of devices that allow for limited production without major reconstitution of existing manufacturing or printing processes. So now, if a major publisher wanted to produce only 1 of a particular book, they could, with little impact on their processes. It would be a poor decision, of course, because it’s better to get a rabid group of fans than one wealthy douche investor. That’s how these 1:100, 1;250, 1:500, up to 1:5000 variants get produced without serious financial repercussions on the publisher. That means that variant with a 1:100 ratio should have a pretty set print run. Ah, but there’s a catch.

Publishers don’t identify that there will be 25,423 books sold and produce exactly 254 books for that 1:100 ratio variant. They’ll produce 250, or 275, or 300. What happens with the extras? Well, shop owners can up their orders afterwards and ask for more books (as long as they’re available), and if they are entitled to them, get a variant they didn’t initially qualify for. Or in some cases, the publisher will make these variants available in other ways, like the infamous Five Below comic book packs.

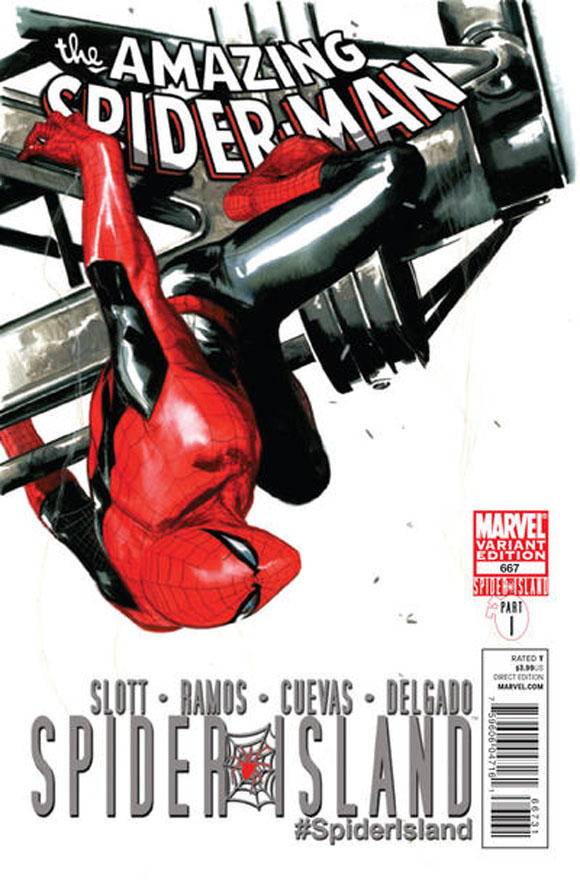

So, the takeaway is, the day of the variant is going nowhere because they are so good at tapping into a consumer-driven desire that came with the concept of capitalism. That’s not a bad thing. It keeps people employed, keeps industries innovating, and keeps the economy chugging along. So, anyone got an Amazing Spider-man 667 Dell’Otto variant they want to part with?

Exactly. I’ve been watching (and speculating and making some money) over the past two years and listening on the G+ communities. What I’ve found is the variant trend is here to stay. Fanboys and gambling speculators will always hunt for the next big thing. Publishers have caught on to the cost effectiveness of the blank variant (no art for the same price or more? Sign me up!). Because blanks drive fans to cons for sketches so the artists are happy. The con promoters are happy. The publisher offers another con exclusive. The comic circle of life.

Well done. (I’d like to recruit you for my upcoming blog, fanboyFRANTICS. I’ll be in touch.)